Part 16 of our series on Important Moments in Team Building. See introduction, and up-to-date list.

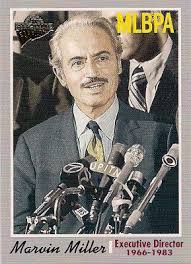

In the 1968 collective bargaining agreement the players union had achieved grievance arbitration, with the commissioner acting as sole arbiter. While this was an important gain, and Commissioner Eckert had ruled in their favor on many issues, an experienced labor negotiator like players’ union leader Marvin Miller understood the importance of getting impartial grievance arbitration into the agreement with the owners.

“[An impartial arbitrator] is the key thing in any labor negotiation,” commented sportswriter Leonard Koppett, “because that’s the only weapon the union has. If you don’t have that, you don’t have anything.” Without a third-party, impartial arbitrator there was no way for players to get a fair hearing. Owners had been acting with impunity, unencumbered by the limitations of the antitrust statutes, since they introduced the reserve clause in 1879.

In negotiating the second CBA agreement in early 1970 Miller hoped to wedge the door open for binding arbitration for player-owner grievances. The owners point person in the negotiation was Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, a priggish attorney who nevertheless loved baseball and was particularly concerned with the commissioner’s mandate to uphold the integrity of the game. Unfortunately for the owners, he also was a neophyte when it came to labor negotiations and didn’t really understand the long-term implications of some of Miller’s approaches. As for grievance arbitration, as long as it didn’t impinge on his ability to rule on integrity issues, he had no real objections. So, among other small but real gains, in the second CBA approved on May 23, an outside arbitrator would now be used for all grievances not involving integrity of the game, an achievement Miller called the “Association’s most important victory,” to that point.

In negotiating the second CBA agreement in early 1970 Miller hoped to wedge the door open for binding arbitration for player-owner grievances. The owners point person in the negotiation was Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, a priggish attorney who nevertheless loved baseball and was particularly concerned with the commissioner’s mandate to uphold the integrity of the game. Unfortunately for the owners, he also was a neophyte when it came to labor negotiations and didn’t really understand the long-term implications of some of Miller’s approaches. As for grievance arbitration, as long as it didn’t impinge on his ability to rule on integrity issues, he had no real objections. So, among other small but real gains, in the second CBA approved on May 23, an outside arbitrator would now be used for all grievances not involving integrity of the game, an achievement Miller called the “Association’s most important victory,” to that point.

As has been noted in several previous posts in this series, under the existence of the reserve clause leverage in salary negotiations was blatantly skewed to the owners. Players had no alternative but to sign with whatever team owned their rights if they wanted to play baseball. With the principal of arbitration in place, Miller and the union next pressed for binding salary arbitration. Under Miller’s proposal, if the two sides could not agree to a salary, the dispute would go to a neutral arbitrator. Arbitration, with its defined criteria for the arbitrator, would force the clubs to play fair and would minimize the inequities among them.

The union successfully pushed through binding salary arbitration in the third CBA, concluded on February 25, 1973. Players with at least two years’ service time would have the right to have their salary dispute heard by a neutral arbitrator. That the newly agreed upon arbitration process was structured as “final-offer” arbitration also benefited the players. In final-offer arbitration, now commonly known as baseball-style arbitration, each side presents its salary request and the arbitrator must pick between them. He only has those two options; he can’t split the difference or pick some third amount. This helped force both sides to be reasonable and try to negotiate in advance—as opposed to taking an extreme position and hoping the arbitrator would split the difference. It also placed the owners in a position of having to negotiate in good faith.

Minnesota hurler Dick Woodson became the first player to have his salary arbitration case heard on February 11, 1974. Woodson asked for $29,000; the Twins offered $23,000. Over an 11 day period, 29 arbitration cases were heard before neutral arbitrators. Another 24 cases were filed but settled before the hearing, an additional benefit of final-offer arbitration. Woodson won his case, but overall the owners prevailed in 16 of the 29 arbitrated cases. Nevertheless, the players were clearly benefiting: even with their losses, 23 of the 29 received raises. Moreover, as Miller had grasped, arbitration forced notoriously tightfisted owners such as Charley Finley to pay competitive wages, increasing the salary scale for everyone. More than one-third of the hearings (10) were for Oakland A’s; nine received raises, some significant.

Minnesota hurler Dick Woodson became the first player to have his salary arbitration case heard on February 11, 1974. Woodson asked for $29,000; the Twins offered $23,000. Over an 11 day period, 29 arbitration cases were heard before neutral arbitrators. Another 24 cases were filed but settled before the hearing, an additional benefit of final-offer arbitration. Woodson won his case, but overall the owners prevailed in 16 of the 29 arbitrated cases. Nevertheless, the players were clearly benefiting: even with their losses, 23 of the 29 received raises. Moreover, as Miller had grasped, arbitration forced notoriously tightfisted owners such as Charley Finley to pay competitive wages, increasing the salary scale for everyone. More than one-third of the hearings (10) were for Oakland A’s; nine received raises, some significant.

For the first time in many years, teams would have to manage around some payroll uncertainty when building their roster for the upcoming season. The final payroll would not be known until all the arbitration decisions were rendered. Team building was about to enter a new era in which creating and managing payroll flexibility would become a significant factor. And a couple years later, its importance would snowball.

[…] 16. Binding Salary Arbitration (1973) […]

LikeLike